BY REUVEN BLAU, THE CITY | This story was originally published on Sept. 23 by The City. New York City’s long-promised 911 texting system has been stalled by a bitter dispute between technology agency officials and the NYPD — with each blaming the other for delays, records obtained by THE CITY show.

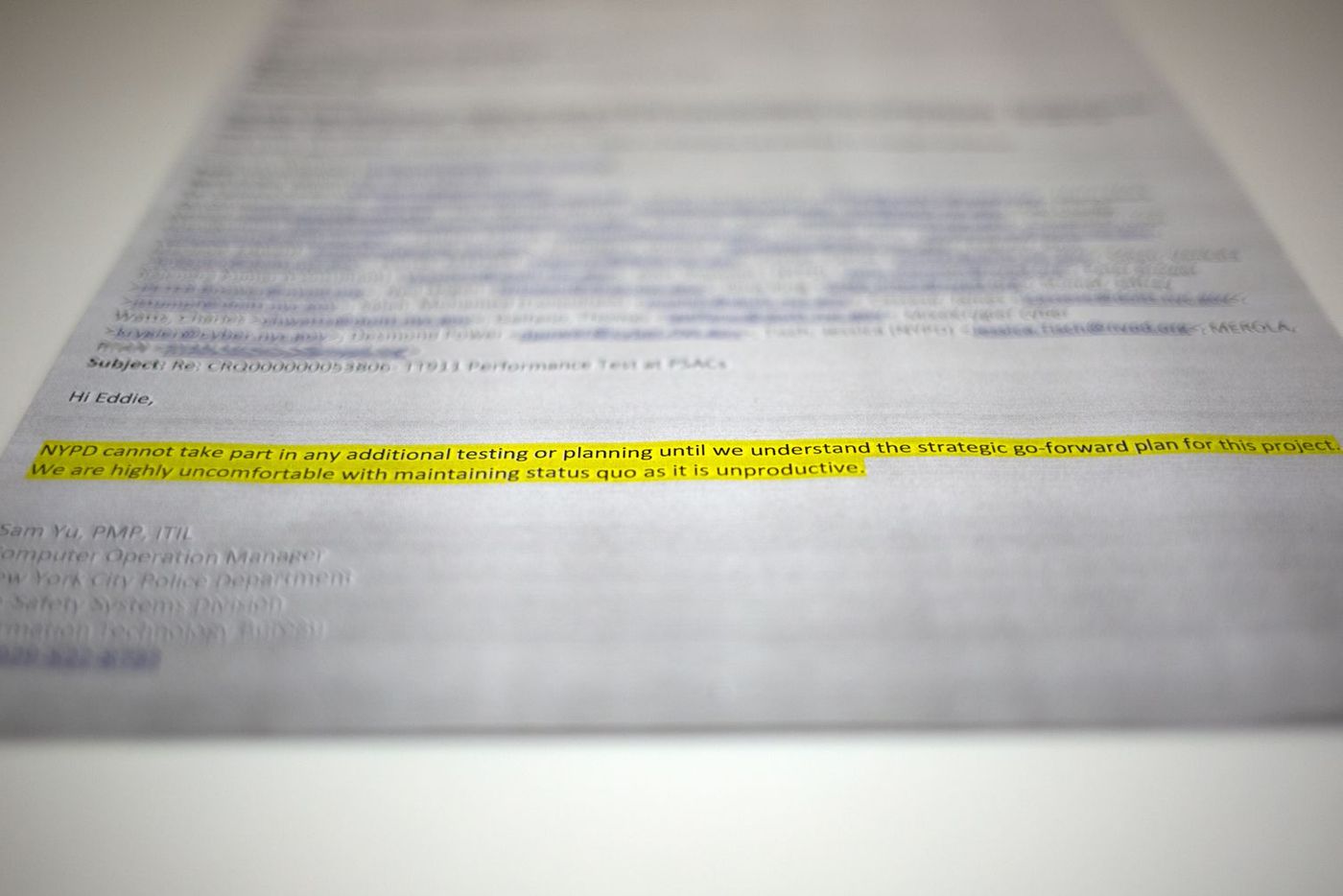

The bickering hit a low point on Jan. 25: The NYPD refused to conduct a new round of testing on the problem-plagued system, according to an internal email.

“We are highly uncomfortable with maintaining status quo as it is unproductive,” Sam Yu, an NYPD computer operations manager, wrote in an email to a group of city technology officials involved in the project.

The missive came weeks after a system test crashed the text network for 24 hours in December 2018, according to multiple sources.

The internal troubles have slowed a potentially life-saving technology announced with high hopes and fanfare.

In June 2017, officials said the planned interim 911 text setup the de Blasio administration promised would be ready by “early 2018.” The texting system, eventually expected to include the ability to accept photos and videos, is part of a larger high-tech upgrade of the 911 emergency call system.

‘Should Have Been Done Already’

But as THE CITY recently reported, the text service is more than one and a half years overdue — a delay that got the attention of Mayor Bill de Blasio and the City Council last week.

“This is something we need to get done, and it should have been done already, honestly,” de Blasio told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Friday. “But I do appreciate there’s a lot of complexities to getting it right.”

The system is now set to be finalized by the middle of next year, he added.

The City Council, meanwhile, has moved up a previously planned hearing into the 911 system upgrade, now scheduled for Oct. 28.

Supporters tout emergency texting as a crucial lifeline for people with hearing and speech challenges. Texting also can give people a safer way to seek help when calling would only increase danger, such as with domestic violence and hostage situations.

More than half of New York’s 62 counties in the state already have emergency texting.

Wide-Ranging Disagreements

City officials are butting heads over everything from the number of call takers to handle texts to how to deal with messages that get lost in the system to what sort of program should be used, according to records and interviews with multiple people involved in the process.

The bad blood dates to the end of 2014 when the texting concept was broached with Mindy Tarlow, the now-former head of the mayor’s office of operations, according to a project history detailed in a Department of Information and Technology (DoITT) report obtained by THE CITY.

At the time, NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Technology Jessica Tisch “would not move forward” with the proposal, DoITT’s June 14, 2018, report to two deputy mayors says.

On Friday, Tisch told THE CITY she didn’t remember that meeting. But she says she was focused at that time on making sure the 911 phone system worked properly following several high-profile breakdowns.

In mid-2016, the NYPD agreed to the proposed plan shortly before the City Council passed a law urging the de Blasio administration to research the feasibility of creating an interim text-to-911 system.

DoITT took the lead, and asked NYPD and FDNY officials to submit “requirements” they wanted to be part of the new system.

Everyone initially agreed the interim system should be a bare bones setup, similar to one in place in Houston, DoITT records show. VESTA Solutions, part of Motorola, was eventually chosen by DoITT to create New York City’s 911 texting setup for $28.3 million.

According to the original plan, written messages would be sent to a so-called text control center, an intermediate between commercial cell carriers and the city’s 911 call centers. The texts would then be funneled through the city’s pre-existing telephone system.

Call takers would have a list of generic responses to use to speed up the process. If something went wrong, they’d instruct the texter to send a new message or to just phone 911.

The first “code drop” — a major internal test of the system — came on June 13, 2017.

DoITT records show it was plagued with defects: Call takers were not logged out after closing the chat window, no buzz sound went off for new chats, and access to archived chats was restricted.

Those seemingly minor issues were just the beginning.

All told, the system under development has experienced at least 68 defects — from chats closing out without warning to computer pages that freeze up — since Dec. 27, 2018, DoITT records show.

A DoITT official involved in the process says the NYPD’s efforts to repeatedly “enhance” the system have been the primary culprit. Each change has created a new set of bugs within the multiple layers of the system, records show.

The NYPD maintains it is merely seeking to make sure the critical system works flawlessly.

‘A Matter of Life and Death’

The deputy mayor currently in charge of the project, after inheriting it from former First Deputy Mayor Anthony Shorris, echoed that view.

“When a New Yorker uses 911, they must know without a doubt that it works,” said Deputy Mayor Laura Anglin in a statement. “This is a matter of life and death.”

By all accounts, the system has struggled to keep track of every text sent to 911. The city did approximately 20 rounds of testing last year, with one resulting in 20% of messages lost or stuck in a queue.

“When we pushed and said, ‘We can’t have any text messages not making it to the call taker,’ that was labeled (by DoITT as) an enhancement,” Tisch said. “That’s not an enhancement.”

DoITT has suggested the NYPD assign a call taker to monitor the text queue to flag any messages that are not sent to dispatchers, according to the tech department source who asked to remain anonymous. That’s how it is handled in Houston.

But the NYPD insists the software must automatically notify officials if a text is lost, dropped, or accidentally ignored, even before the rollout of a bigger 911 upgrade.

“When I think of the word ‘interim,’ I think of stable, robust, text to 911 system that New Yorkers can rely on,” Tisch said.

Further complicating the matter is that Houston uses separate systems for 911 phone calls and texts. The New York City system is set to be intertwined, a more complex arrangement that has led to some of the delays.

A major point of contention is how the emergency system will deal with an “unplanned event,” like a mass shooting or a huge storm, that generates a massive spike in 911 messages.

The NYPD insists the system must be able to handle 200 texts at any given time, according to Tisch. DoITT officials say that’s not a problem.

But the test in December, run by computers, flooded the system with individual text messages at a rate of one per second. Normally, a real person messaging the system would not follow up with a new text a second later, DoITT officials pointed out.

Software Update Needed

The Police Department and DoITT are also at odds over who will handle texts and how. The NYPD initially wanted a group of about 300 of the city’s approximately 2,000 911 call takers to be trained in how to deal with text messages, according to the DoITT source.

The Police Department has since trained all of its call takers, but the delay will likely force everyone to get a refresher course before the system’s launch, according to Tisch.

Call takers were initially expected to tackle calls and texts during each shift. But the system is now set up so that they will either be able to handle calls or texts. That will force the city to figure out staffing.

Text pleas typically take four to seven minutes to deal with, given typed messages back and forth, according to other jurisdictions’ experience with the technology. That’s far longer than the 30-to-120-second average for 911 phone calls.

As for the broader system, it is unclear when the next round of comprehensive testing will begin. The city’s so-called cyber team is currently trying to ensure the software can’t be hacked.

The delays have gone on for so long that some of the software is already outdated, and DoITT officials are concerned that upgrades are already needed.

Meanwhile, a pending federal lawsuit by Disability Rights New York, is pressing the city to launch the system for New Yorkers with hearing issues. That case has been snaking its way through court since 2017.

City officials are sympathetic.

“I’m one of the biggest proponents of text-to-911,” Tisch said. “I’m so eager to have it go live and to have it be a real asset to public safety.”

But, she added, “You can’t put out a system that’s going to crash when lots of people are using it.”

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.