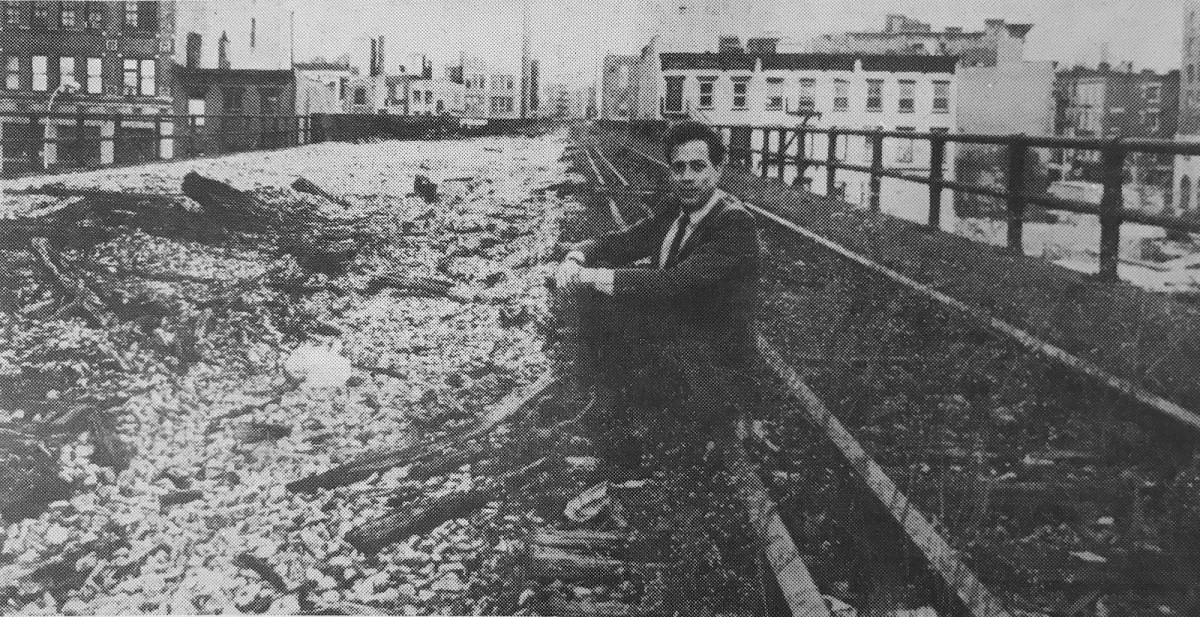

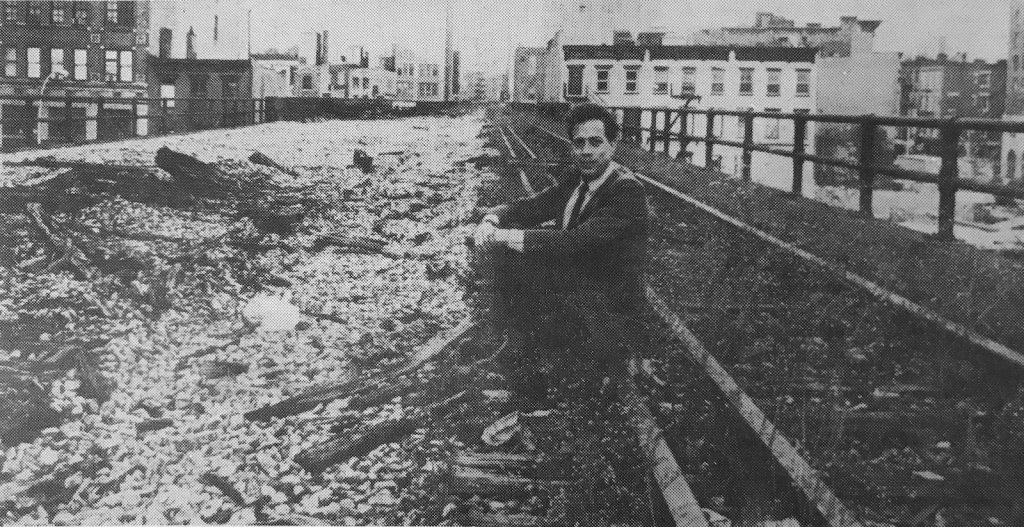

BY GABE HERMAN | The front page of The Villager on Jan. 7, 1982, featured a profile of Peter Obletz, who for years advocated to save the High Line from demolition and reuse it for transportation and recreation.

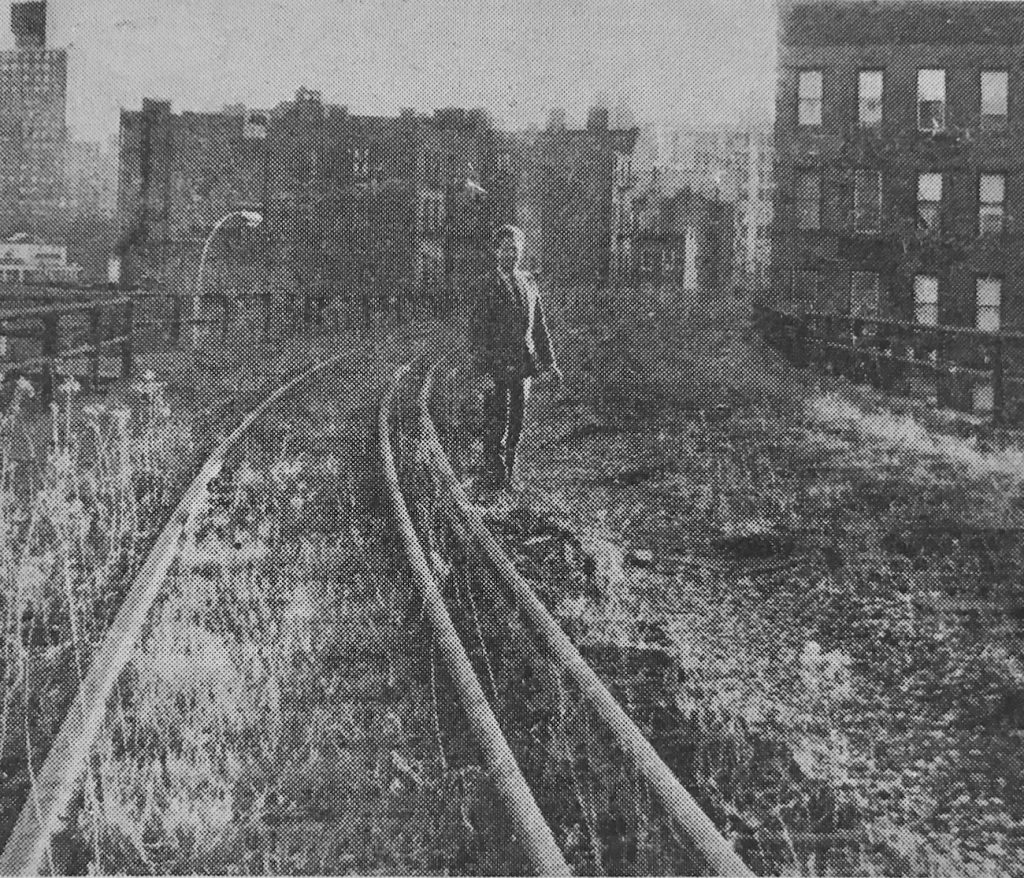

At the time, the elevated freight rail line was abandoned and overgrown. Train use for transporting goods had declined starting in the 1960s with a rise in trucking.

By the ’80s, train traffic on the High Line had ceased completely. The southernmost part of the High Line, between Spring and Bank Sts., was demolished in the ’60s, and calls grew into the ’80s for the remainder of the structure to be razed.

But Obletz told The Villager that he wanted to save the viaduct. One of his ideas was for a sleek railroad car that would make leisurely trips to a new railroad museum, as it passed community gardens and concession stands along the High Line. Another was for a trolley car that would made regular stops along the line, for use by local Chelsea and Village residents.

Obletz saw his schemes as helping address transportation needs in an area undergoing a surge of development.

“These ideas are not for any crackpot sentimental or historical reasons,” he said, in the article by Elizabeth Weiner.

The train enthusiast was a West Chelsea resident. The Villager article described him “sitting in his renovated stationmaster’s quarters under 11th Avenue, with his two vintage private railroad passenger cars sitting on the tracks outside like faithful guardians.”

Obletz, then 35, had been a consultant to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Sweet 14, a local development corporation for E. 14th St., and was chairperson of Community Board 4 in the 1980s.

He was also a partner in a private luxury rail tour company backed by American Express. Obletz told the newspaper that his personal interest in trains “became so intermeshed with the political and economic development of Manhattan that I had to get involved.”

His efforts to save the High Line included forming the West Side Rail Line Development Foundation in 1983, and buying the High Line for just $10 in 1984, which was eventually overturned in court. Obletz died in 1996 and didn’t get to see the High Line park.

“He was the first saint of the High Line,” Joshua David, a co-founder of Friends of the High Line, told The Villager in 2013 about Obletz.

Another article, on Page 3 in the same issue, described continuing problems on Bleecker St. from excessive truck traffic, largely stemming from the Abingdon Square intersection.

The problems began in 1957, according to the article by Carol Hall, Manhattan’s two-way avenues were changed to one-way arteries. At the busy Abingdon Square intersection, which includes Bleecker and Hudson Sts., and Eighth Avenue, “traffic that once whizzed past now veered from southbound Hudson onto Bleecker,” the article said. “The result was a greater number of accidents and increased congestion on an already bustling street.”

Despite street signs saying that Bleecker was only for local deliveries, all manner of trucks, and even airport-bound tour buses, seemed to be barreling down Bleecker.

“I don’t think the street is made for this,” Stephen Kutay, owner of Eastern Arts on Bleecker, told The Villager.

Ads in the issue included The Candle Shop, at 118 Christopher St.; Garber’s Hardware, which is still in business today and was founded in 1884; and the recently released “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” showing at the 8th St. Playhouse at Sixth Ave.