BY GABE HERMAN | The city recently announced a record 65 million visitors last year, the ninth straight year of increased visits. This was hardly surprising for locals, who see the streets and city’s great institutions get more clogged by the day.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one such crowded gem of the city. Its 7 million yearly visitors all seem to be in the way, blocking views, jostling and preventing you from enjoying a good, long look at the great collections.

But there are ways to avoid most of the crowds and get the most out of a Met visit. Veteran museum workers recommend finding breathing room in some of the best but often overlooked areas like the Islamic galleries, modern art and a quiet Chinese garden court.

Hopefully, locals already know to enter through the Met’s side entrance at E. 81st St. This entrance usually has much shorter lines for admission and coat check, according to Dr. Grazia Montesi of the Met’s information services.

“If you’re meeting friends, meet down there,” she said.

A short elevator ride will bring you to the second floor and right next to the Islamic art section. Tour guide Nancy Posternak said this wing is under-appreciated. Its works span 1,300 years and include large, colorful and finely detailed carpets, some spanning across an entire wall.

There is a mihrab, or prayer niche, from 14th-century Iran with intricate arabesque and calligraphy designs. And ceramic tableware features geometric patterns in vibrant blue colors that jump out at you.

“The Islamic galleries I think are really under-seen,” said Posternak, who has been a guide for nearly 15 years. “They are really spectacular.”

It is a short walk from Islamic art to the Met’s modern art collection. Montesi said this area includes many great works but is not often crowded because it is tucked behind the popular Impressionist wing.

A highlight in the modern art section for Posternak is Picasso’s “Reading at a Table” from 1934. It depicts Picasso’s lover and model Marie-Therese Walter, painted in pastels and with the signature Cubist elements of broken images and a flat depth of field.

“We can see his tenderness for her in the color choices he’s made,” Posternak said. “It’s just great, very simplified.”

Next, go down to the first floor for some of the Met’s smaller rooms. Such spaces are practically hidden, according to tour guide Charles Mayer. It isn’t a question of people not liking them, he said. Rather, he noted, the rooms can be tucked away from the large main hallways, “so you don’t know to go there.”

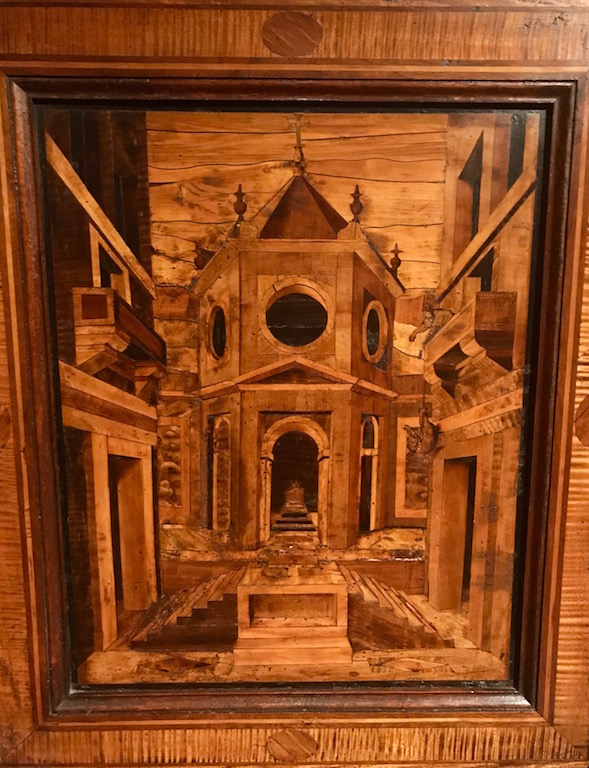

Two such rooms are in the Italian Renaissance wing. The rooms feature intarsia, a method of inlaying wood of various natural colors to create images. One space contains work from a 16th-century chapel and includes stained-glass windows and intarsia images on the walls that are detailed enough to be paintings.

“It’s kind of off the track,” Mayer said. “You’re headed toward Arms and Armor, you’re not aware it’s here.”

Just next to the chapel is an even smaller space, a 15th-century studiolo, or study room, that also features intarsia wooden inlay. Only a few people can fit at a time, so Mayer can only take tours to the chapel room. But the studiolo’s artwork is greatly detailed, and Mayer said it makes the chapel room “look amateurish.”

The studiolo was just recently discovered by a longtime regular visitor, Sandra Pappas, who has been coming to The Met for 40 years and lives a block away. Her advice is to always keep your eyes open in The Met for a new discovery.

Even in the crowded Great Hall at the museum’s entrance, Pappas loves the five huge bouquets of flowers that are replenished every Tuesday and change with the seasons. Sarah Wilhelm, of the museum’s Member and Visitor Services, loves them, too.

“The Halloween ones are the best,” she said, noting they feature large orange puffy bouquets surrounded by pumpkins.

“Sometimes I come just to see the flowers,” Pappas said. She added, with a smile, that she has occasionally heard crickets in the bouquets. “Once I even saw a frog jump out of one.”

The museum’s Impressionist and Ancient Egyptian wings tend to be the most crowded, according to Wilhelm. She wishes more people would visit the Asian art section on the museum’s third floor, and in particular the Astor Chinese Garden Court. The space is large and naturally lit through a high glass ceiling. Patches of the ground have been filled with soil and plants, and are surrounded by groups of large jagged stones. Running water can be heard from a koi pond in the corner, which Wilhelm especially likes.

“It’s so peaceful there,” she said.

Another work with running water is “Water Stone,” by Isamu Noguchi, from 1986. It features one large stone with many small rocks scattered about, all of which came from Japan. Nearby seats make it a good place for a rest from museum walking, which is somehow much more strenuous than ordinary walking. Fans of this work can also visit the Noguchi Museum, which features his work exclusively, in Long Island City.

Wilhelm said that museum visitors should be willing to explore and find sections like the Asian art wing.

“People tend to stick to the same areas, which is a shame,” she said. “But the Asian art is beautiful.”