BY JACKSON CHEN | The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) took another step in the lengthy approval process for its controversial expansion as the Department of Parks and Recreation released the project’s draft environmental impact statement on May 18.

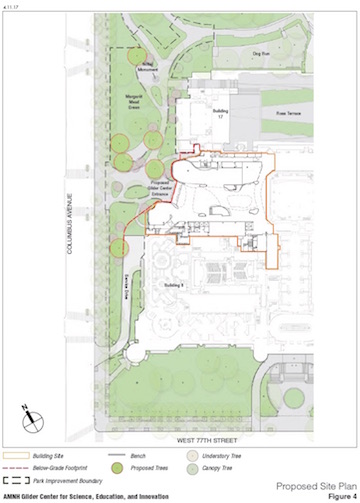

The Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation comes with a $340 million price tag and would significantly improve the museum’s visitor flow and offer more exhibition and educational space. However, the project would also encroach on the surrounding Theodore Roosevelt Park and involve three years of construction.

The dense and detailed draft environmental impact statement (on.nyc.gov/2qc5UE0) triggers a comment period, with the public given the opportunity to sound off on June 15 at 6 p.m. in the museum’s LeFrak Theater (enter on Columbus Avenue at West 79th Street).

According to Ed Applebome, senior vice president at AKRF, an environmental consulting firm that was part of the project team, the document focuses on changes between the site’s existing environment and expected conditions once the project is completed, with particular focus on three areas with potential for significant adverse environmental impacts.

The expectation that the Gilder Center will draw an additional 745,000 annual visitors to the museum means there will likely be a notable impact on traffic and transportation. Applebome said that looking at three intersections expected to see increased vehicular traffic — West 81st Street and Central Park West, West 77th and Central Park West, and West 77th and Columbus Avenue — the team concluded that impact can be mitigated by a one-second traffic signal retiming at the discretion of the Department of Transportation. To address the expected influx of pedestrians at West 81st Street and Columbus Avenue, he added, a widening of the painted crosswalk is recommended.

In weighing the impact of three years of construction, Applebome said the team specifically looked at two residential buildings — at 101 and 118 West 79th Street — in particularly close proximity to the project. There, the museum is exploring mitigation techniques like window treatments and air conditioning to reduce the negative effects of construction noise and pollution on residents.

The museum will also establish a construction working group to field concerns and complaints and serve as a point of contact for the community and local leaders. According to Dan Slippen, the museum’s vice president of government affairs, in assembling this working group, the museum will cast a “fairly wide net and we’ll be pretty inclusive” — potentially with representatives of neighborhood or block associations and business improvement districts.

Due to the demolition of one of the museum’s existing buildings, one significant impact on historical and cultural resources cannot be avoided, Sue Golden, a partner with Venable LLP, a law firm that was part of the museum’s team, acknowledged. She noted the museum would document the building’s existence by preserving its records and working with the State Historic Preservation Office.

Vocal opponents of the project remain vigilant, having rejected the Gilder Center at every step. Cary Goodman, a District 7 City Council candidate, was critical of the methods and documents used to examine the project. He said his stance remains the same — that the museum should restart the entire process with community input at the fore.

“Frankly, I don’t think they have the community’s interest at heart for me to trust them to contain all the toxins that’s part of the project,” Goodman said of the environmental impact. “I’m not clear that their level of commitment to the neighborhood is good.”

Another opposition group, the Community United to Protect Theodore Roosevelt Park, recently retained an engineering firm through Michael Hiller, an attorney known for representing residential opposition to major developments, according to the group’s president Claudia DiSalvo. She added that the firm’s independent study would be more comprehensive compared to the draft study completed by the parks department.