BY STEVE SLAVIN | I’ve been a runner since high school. In fact, Bernie Sanders and I ran cross-country for Brooklyn’s James Madison High School. Almost every Saturday morning in the fall, more than a dozen of us would meet at the Kings Highway subway station to make the two-hour trek to Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.

Bernie and I had not seen each other for more than 30 years when he spotted me at a fundraising party being held for his first Senate campaign. His first words were, “Still running?”

Bernie had been one of the best high school distance runners in the city, but when his mother fell very seriously ill during his junior year, he gave up running. There’s no telling just how good he might have become.

As for me, I’m still running. My times are not nearly as good as they had been in college, but my proudest personal best is having done two round trips over the Brooklyn Bridge in just over 29 minutes. Of course that was long before the bridge was discovered by hordes of tourists.

Back in the 1960s, New York — as well as other cities — had not yet become such runners’ paradises. And the pedestrian paths of the bridges were virtually empty. Runners were considered oddities. Occasionally someone might call out an insult, as if we were the deviants.

Once, when I was on the Williamsburg Bridge, some teenage jerk yelled out something really stupid. I called back, “Your good looks are rivaled only by your high intelligence.” Imagine his stunned look.

I had a neighbor, Clarence Richie, who ran 26 miles twice a week, just for the fun of it. He turned me on to his bridge run, which he did on his “easy” days.

We lived on the Lower East Side, just off Delancey St., so we began our run on the Williamsburg Bridge. From there we headed along Myrtle Ave. to DUMBO and then over the Brooklyn Bridge. Once again in Manhattan, we threaded our way through Chinatown and back to the Lower East Side.

If the Brooklyn Bridge had just a handful of pedestrians, the Williamsburg Bridge was almost totally deserted. I rarely encountered more than one or two people when I would do my usual round trip. But my fondest memory was when a guy asked me for a cigarette.

Later, I thought of an answer, which actually made no sense: Don’t you know that running is bad for smoking?

There were even fewer people on the Manhattan Bridge. I ran across just a few times and don’t remember seeing a soul. It was kind of creepy, but that still didn’t compare with the stretch at the Brooklyn entrance to the Williamsburg Bridge, where you had to run about 15 feet below the subway tracks.

Sometimes people ask me if I ever ran a marathon. The answer is “yes and no.” Back in 1962, I did run in Boston. I was 22, and should have been in the best shape in my life. But I was working full time, going to grad school at night, and also attending occasional Army Reserve meetings.

That did not leave a lot of time of training. In fact, the best I did was one or two 5-mile runs a week. To this day, I am embarrassed to admit that.

My race strategy was on a par with my training regimen. I would go out fast and hold the lead as long as I could. Because there were just 181 runners, this would be possible. I did go out fast — much too fast. I led for a few hundred yards, but then I got a terrible stitch in my side. I was clutching my ribs as runner after runner jogged by. Soon I recovered, but now my goal was just to finish. I remember reaching the 5-mile mark in Framingham, the 10-mile mark in Natick. But by then, for the first time in a race, I had stopped running.

I would walk for awhile, and then start jogging again. I passed the halfway mark near Wellesley College, but I knew that I would never make it all the way. My feet were blistered and I was dead last, far behind the guy in 180th place. A few minutes later, a kindly driver offered to take me to Boston.

Just an hour after the first runners crossed the finish line, the Boston papers had the results of the race. Here are the words in the second paragraph of a first-page story:

“The fleeting glory of leading the pack went to Steve Slavin of Brooklyn. He was instantly pursued by Kurt Steiner. After a quarter mile Slavin clutched his side and dropped back, evidently because of the fast pace he had set.”

When I showed the clip to Clarence and his good friend Teddy, the two of them burst out laughing.

“What’s so funny?” I asked. “You’re laughing at me because I went out so fast?”

They just shook their heads, and couldn’t stop laughing. Finally, they were able to explain why the article was so funny. It turned out that Kurt Steiner was well known for sprinting into the lead at the start of marathons.

Then Clarence added, “You must have gone out of there like a bat out of hell to beat that guy!”

Maybe 30 years later, I heard that Kurt Steiner was the director of a road race I’d be running in. I walked over to him and asked, “Mr. Steiner?”

“Yah?”

He was in his late 60s or early 70s, and had what appeared to be a German accent.

I handed him the clipping. A few seconds later he growled, “You vere zuh guy!!!”

On a beautiful late spring evening this year, I had just left an opening on Suffolk St. that was exhibiting my friend’s paintings. l decided to walk over to the Williamsburg Bridge. As I approached the walkway entrance, the light changed, and maybe 50 or 60 cyclists, and eight or 10 runners — all of them very businesslike —made their way onto the bridge.

In the 1960s, there had been just one pedestrian walk on the left, but now there were two cycling paths and two running and walking paths on the right. It cheered me to see these changes, and that so many people were running and cycling over the bridge. As I walked to the subway, I made myself a promise that I would come back here and run over the bridge. But maybe when it was not so crowded.

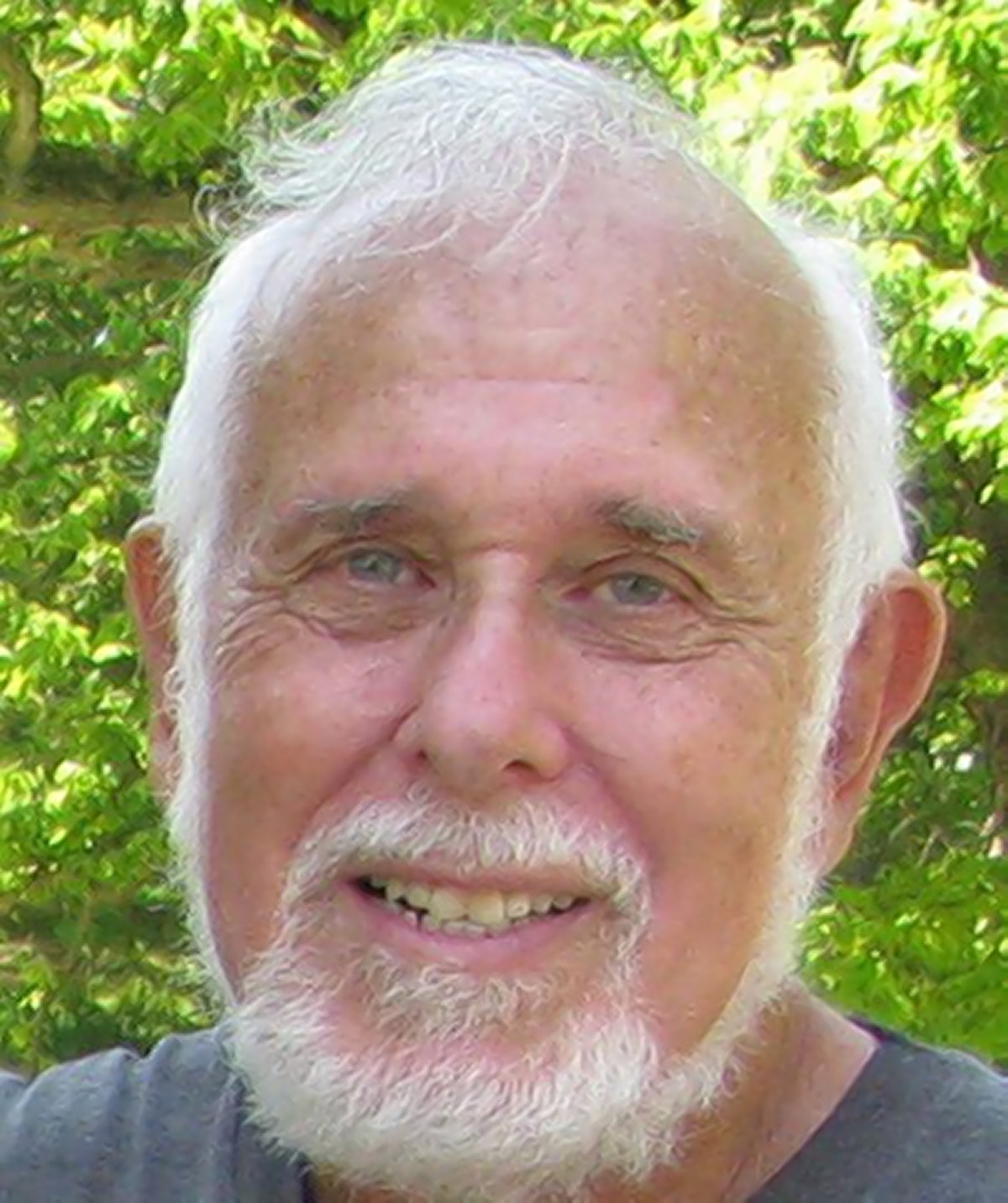

Slavin, who has published 16 books on math and economics, recently published his first collection of short stories, “To the City, With Love” (Martin Sisters Publishing)