BY PERRY N. HALKITIS, PhD, MS, MPH | When asked about why I teach my HIV prevention and health promotion course at the New York University London campus each January, I am quick to indicate that I want my students to experience the delivery of health care and examine public health programming under the National Health Service (NHS) — a system of great pride to the British, and often heralded as of the best in the world. There is no falsehood in this statement and this conception serves as the foundation for the course.

However, I would be disingenuous not to mention that this course provides me the opportunity to spend two intensive weeks working with some of the university’s most dedicated and talented graduate students — those working in public health dedicated to the eradication of this disease, driven by a social justice agenda, and firm in the belief that HIV/AIDS, like so many other diseases globally, is driven by social and structural inequalities, and in our country is fueled by poverty, racism, and homo- and transphobia. As a result, we not only study the epidemiological, biomedical, behavioral, and policy aspects of the HIV epidemic, but also engage in thoughtful conversations of power and privilege.

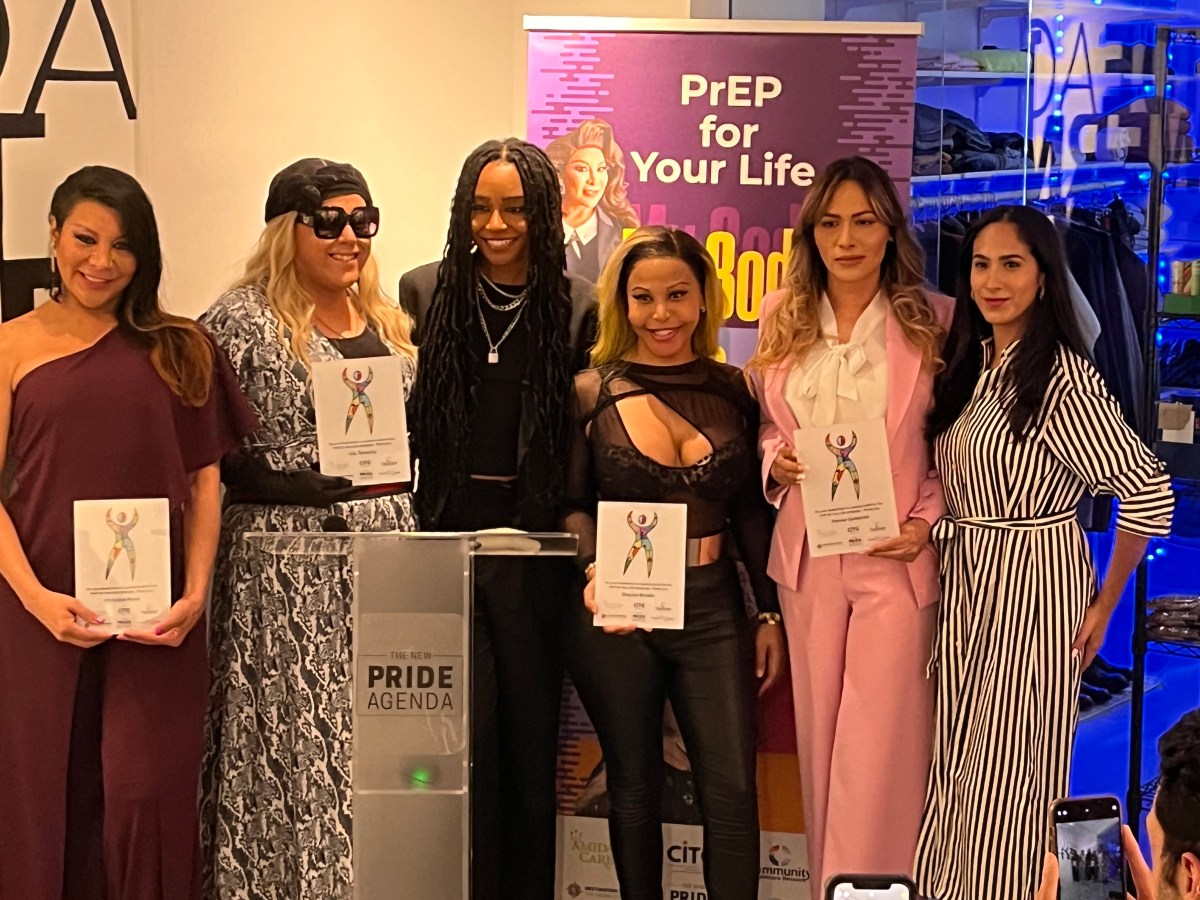

To bring this learning to life — and to bring a public face to these studies — students engage in active learning throughout the two-week intensive course. They interact with staff and clients at AIDS service organizations, having open and honest conversations with many living with HIV. They speak with public health leaders about the effectiveness of health programs and messaging; they hear from the health care providers and patients at clinics, while visiting the facilities; and they learn from some of the nation’s leading researchers who, like myself, work to bring our scientific knowledge immediately to the people who need it most.

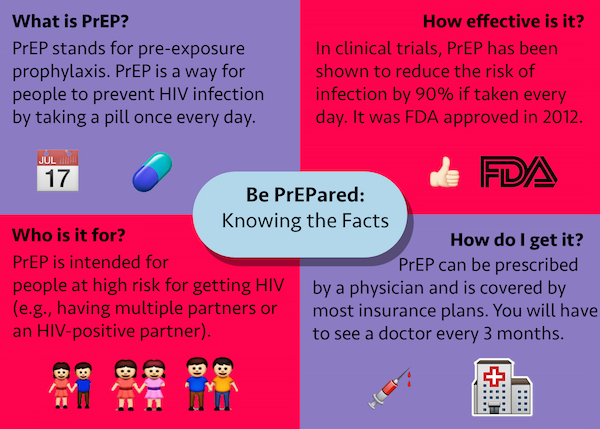

This year, Will Nutland, an HIV research fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, spoke of his studies on PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; a daily pill regimen meant to prevent HIV infection] in the United Kingdom, and his concurrent activism as one of the founders of PrEPster (prepster.info), a public website that provides information and guidance to those seeking to access this prevention tool while the NHS debates its merits (the NHS has yet to approve Truvada for use as PrEP).

It is within the context of the course that students are asked to examine how the principles, knowledge, data, and theories that they are studying can be used to improve the lives of so many. It is also with this notion in mind that the course assignments are designed, utilizing an action-based learning paradigm and rooted within the students’ inherent passion and commitment to health equity.

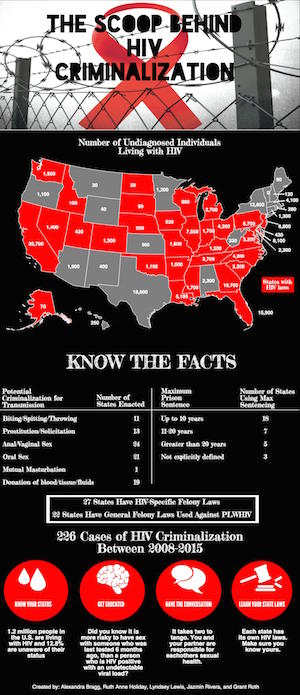

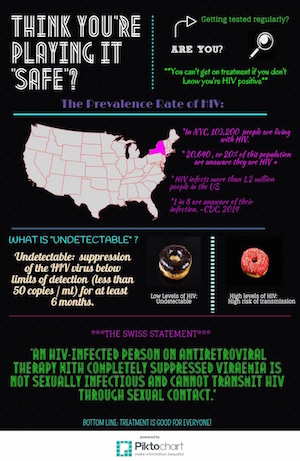

This year, the 37 students were asked to work in groups to develop a public service announcement and an accompanying infographic on any area of HIV prevention targeted to any population in the US or UK. In short, they were asked to bring their learning to life for the health of the public.

What emerged was a set of thought-provoking, provocative, and often boundary-pushing campaigns that informed the current biomedical, behavioral, and socio-political drivers of the HIV epidemic that they had studied. They also chose areas that were personally meaningful to them, allowing them to integrate the wide range of knowledge they had developed with their own commitments to social justice and compassion for those infected with and affected by HIV.

The products that the students created advance our dialogue about HIV and underscore the idea that in our dedication to public health, we must be ever-evolving in our thinking and approaches. The HIV epidemic of 2016 is not that of 1986. In effect, the health challenges of each generation must be understood in relation to time and the particular struggles that each generation faces. Finally, these infographics serve to remind us that public health programming and research must be developed with, and for, the public — and with compassion to the realities of human life, summarized with great clarity by MPH student Jazmin Rivera:

“In academia, we are often surrounded by a bubble of abstraction. We study a health problem, we find a biomedical or behavioral intervention, we implement it and then we wonder why it fails. Public health is about people; HIV is a disease surrounded by inter- and intrapersonal stigma. We have to be mindful of the human experience when we plan programs and interventions. That is what public health is about. ”

Perry N. Halkitis is Professor of Global Public Health, Applied Psychology, & Medicine, and Director of the Center for Health, Identity, Behavior & Prevention Studies at the College of Global Public Health, New York University (@DrPNHalkitis; perrynhalkitis.com).