BY COLIN MIXSON | This month’s launch of a Barneys New York in Chelsea has been hailed as a return to its famed Seventh Avenue roots, at the very spot where Barney Pressman pioneered the original, flagship Barney’s — apostrophe and all — after pawning his wife’s engagement ring for $500, which he parlayed into a fashion empire. But, for some longtime Chelsea residents, the thought of Barneys’ homecoming doesn’t manifest itself in the anticipation of great deals on the latest fashions. Instead, it conjures largely forgotten memories of outrageously theatrical protests in front of a burgeoning retail juggernaut, which was determined to expand throughout the neighborhood — no matter what the cost.

“It’s been absolutely forgotten,” said Penn South resident and veteran Chelsea activist Gloria Sukenick, 91, a stark opponent of the original Barneys. “They’re talking about Barneys like it’s some gift from the gods,” she said of recent press coverage heralding the store’s return. “But they had a lot of enemies in Chelsea.”

By 1981, Barneys had outgrown its Seventh Ave. digs, and the luxury men’s clothing merchant was prepared to expand into the more lucrative realm of feminine attire. Towards that end, the store was eyeing two properties around the corner on the 100 block of W. 17th St. (btw. Sixth & Seventh Aves.) as the home for its inaugural women’s department. But there were a few challenges facing the retailer’s expansion, first and foremost of which was the acquisition of a special permit that would allow Barneys to operate on property originally zoned for light manufacturing.

The authority to grant this zoning allowance was then invested in the Board of Estimate, a defunct city agency legislated out of existence in 1990, whose powers were reinvested into the City Council. Leading up to that vote, however, the department store was first obliged to seek out a recommendation from Community Board 4 (CB4) — and it was there that Barneys found itself mired in opposition.

The acquisition of the property that would become Barneys’ first women’s department was not merely a matter of dollars and cents: The deal necessitated the removal of seven families, who enjoyed rent-stabilized apartments, and who paid a mere $90 and change per month for their W. 17th St. residences. Those families had little hope of finding other apartments in the neighborhood at a similarly affordable rate, and their displacement would have likely meant bidding farewell to Chelsea altogether, according to a Chelsea Clinton News article (“Landmark Barney’s Case Agreement: Businessmen Happy, Tenants Saved,” June 17, 1982).

The prospect of families living on meager incomes paying the price for Barneys’ expansion certainly didn’t sit well with local activists, according to one longtime Chelsea resident.

“They were living there, and they were forced out,” said Roberta Gelb, a Chelsea resident since 1977. “And for what? So rich women could shop with their husbands?”

The seven families received support from the community largely in the form of the Chelsea Coalition on Housing (CCH) and its late founder Jane Wood, a legend among local activists, who even now speak in awe of her ability to summon and organize hordes of local protestors.

“Jane Wood, she had all of Chelsea behind her,” said Sukenick. “One phone call from her, and people would turn out and fill a block. She saved a lot of people their homes, and she had a lot of intense loyalty.”

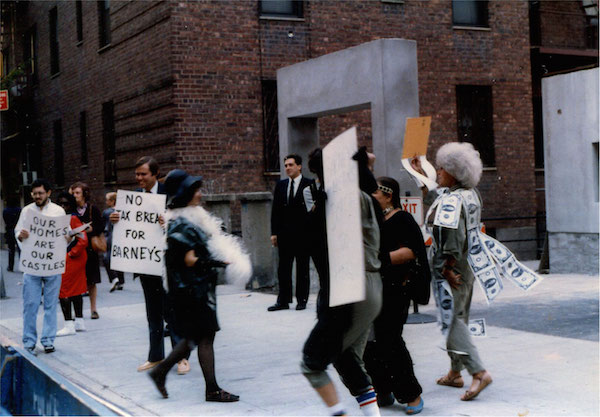

Galvanized by Wood and the shabby treatment of their neighbors, an alliance of activists (working under the group name “Blockeye on Barneys”) headed to the sidewalks outside of Barneys, in protests taking the form of street theater — with all the exuberant, attention-getting visuals that term implies.

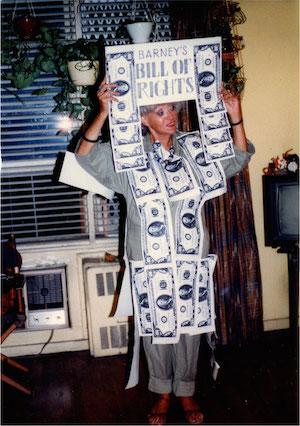

One of the group’s first demonstrations occurred during a fashion show at Barneys, with the protestors sporting avant-garde attire inspired by their loathing of the department store, according to Sukenick.

“We hired a limo and we dressed up in costumes,” she recounted. “I had a jumpsuit with big dollar bills on it that said, ‘Barney’s Bill of Rights.’ ”

The housing coalition, and its civic allies in particular, always celebrated holidays with theatrical protests.

On Thanksgiving, protestors wearing turkey suits appeared outside the department store to hand out fliers bemoaning the store’s expansion; during Easter they donned bunny suits; on Christmas, there was none other than Old St. Nick himself demonstrating outside Barneys, according to Gelb.

The protests led CB4 to vote overwhelmingly in opposition to the department store’s coveted special permit, and the Board of Estimate followed suit. In response, Barneys was forced to make good with the community.

The store found accommodations for five families two blocks away, on W. 17th St. btw. Eighth and Ninth Aves., and established a trust that would pay the difference on their rent for 12 years and six months, according to a Chelsea Clinton News report (“Barney’s Agrees To Rent Trust Fund”). Another family was paid off outright as part of the deal, while the remaining tenants continued to hold out. It is unclear if any restitutions were made by Barneys on their behalf, according to the report.

The deal largely satisfied all parties. The tenants’ concerns were, for the most part, assuaged, Barneys received the special permit it required to move forward with their expansion, and the protestors declared victory in their yearlong struggle with the department store, according to Randy Petsche, who demonstrated with, and handled press for, the CCH.

“It showed the potency of the issue of tenant relocation and such,” said Petsche, who has lived in Chelsea since 1978. “That one was clearly a win.”

A legacy of that victory, Mary Rentas, who was nearly forced out of Chelsea amidst Barneys’ controversial expansion, still lives in that same apartment on the 300 block of W. 17th St., where Barneys footed the bill for more than a dozen years, thanks to the community’s ardent support.

But the coalition’s victory over Barneys would presage many years of perceived abuse at the hands of the growing department store, and, beginning in 1984, new construction occurring a block south on W. 16th St. would reignite the simmering tension between Barneys and its neighbors.

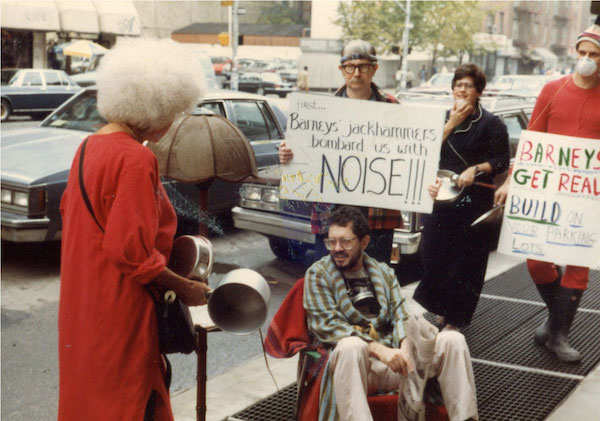

This time, the point of contention was off-hours construction, which began early in the morning and continued late into the night — raising a literally deafening racket, as one neighbor described in Eve Ottenberg’s “Hard Times” column in the Village Voice (“Barney’s Blasts Chelsea,” Apr. 3, 1984).

“Pumps, compressors, earth-movers, jackhammers. I can’t hear my stereo, my telephone, my smoke detector. It’s impossible to maintain a normal conversation,” then-141 W. 16th St. resident Stanley Koven told the Voice.

Once again, Wood’s Coalition on Housing jumped into the fray, and soon protestors were outside Barneys creating their own racket, Gelb recounted.

“We were so upset, the first skit we did was all about Barneys making noise,” said Gelb of an Oct. 20, 1984 demonstration. “We were banging pots and pans, and it was very much street theater. Of course we had props: chairs and a lamp, and somebody in a robe; and Gloria came out with curlers in her hair. It was very quiet, she was reading a paper, and then all this noise started. We got very creative after that.”

The activists enjoyed some success, insofar as earning the ire of Barneys employees, according to Sukenick.

“We made their lives miserable. The Barney boys were standing behind their glass doors glaring out at us. If looks could kill…they were very unhappy,” recalled Sukenick, who was intimately familiar with the noise and poor air quality generated from the Barneys expansion project (she lived at 125 W. 16th St. during that time, then moved to Penn South in 1991).

However, Barneys would ultimately win out in this second contest. Similar to the first struggle, the protestors were hoping to leverage Barneys’ desire for a new suite of special permits it required through the Board of Estimate for the W. 16th St. expansion, but, despite the community’s blatant misgivings, the board would ultimately award Barneys the zoning allowances it required in 1985, according to Petsche.

“Once they got their permits from the Board of Estimate, that ended with a certain amount of bad feelings on that block,” he said. “But that was done. It was a done deal.”

After all the hardships endured and the struggles fought, the community would ultimately be liberated of Barneys courtesy of forces beyond their control. The retailer reestablished itself with an even larger flagship store in more fertile shopping grounds uptown in 1993, and would abandon its Chelsea franchise altogether in 1997.

“The irony was that, not long after, they closed up and moved uptown and left an empty building. After all that destruction they turn around and leave the community,” said Gelb. “Now they’re back again.”

Barneys has now returned to a much different Chelsea than it left in the ’90s. Certainly, the kind of low-income families that formed the backbone of the neighborhood’s age-old beef with Barneys have long fled the neighborhood in the face of gentrification, and outrageous rents that dwarf the $90-per-month paid by the families the store sought to displace in ’82.

However, the move back to Chelsea has stirred up a whole new pot of community tension. In particular, Barneys’ dealings with the 100 West 16th Street Block Association, which it had negotiated with in late 2015 in pursuit of the block’s support for a liquor license the store required for its third-floor cafe, Fred’s, has left a bad taste in the mouths of nearby residents.

In speaking with Barneys’ lawyers, eight-year block association member and current president Paul Groncki made it clear that the block’s support was contingent on numerous conditions, an important component of which was that no deliveries, food or non-food, should occur on the narrow W. 16th St., Groncki said.

In fact, a draft agreement undersigned by Barneys representative Marc Perlowitz, which included the stipulation banning deliveries on W. 16th St., left the block association feeling as though this Barneys was new in more ways than one, Groncki said.

“I shared that agreement with everyone on the block association. Everyone was thrilled, and we thought maybe this new Barneys is a good Barneys,” he said.

Having spoken and shaken hands with Barneys reps, Groncki and his block association felt secure in what appeared to be a firm promise from the retailer. As a result, block residents, including Groncki, who handled negotiations with Barneys, didn’t feel any need to appear at a subsequent meeting of CB4, which is ultimately responsible for conveying and, in effect, ratifying the neighborhood’s stipulations with the State Liquor Authority (SLA) — a big mistake.

Amongst the stipulations sent to the SLA in return for the community’s blessing, the condition that no deliveries be made on W. 16th St. was conspicuously absent. Adding insult to injury, the store posted a notice at its main entrance on Seventh Ave. that all deliveries were to be sent to — you guessed it — W. 16th St.

“They just lied to our faces,” said Groncki. “They agreed to all these stipulations, and so we didn’t show up in force at the community board.”

Jesse Bodine, CB4’s district manager, said he sympathized with Groncki’s sentiment that Barneys had outmaneuvered him, but conceded that the Business Licenses & Permits Committee — which is accustomed to more drawn-out negotiations than other CB4 committees — ultimately gave the store its blessing after Barneys reps said they could agree to all the stipulations worked out with the West 16th Street Block Association, save the condition regarding deliveries.

“That was the one thing they would not agree to,” said Bodine. “But when somebody comes in and agrees to nine out of 10 stipulations, that’s usually pretty good.”

According to a Barneys spokesperson, the whole episode was an honest misunderstanding. The attorney who dealt with Groncki had confused an agreement between Barneys and its building’s co-op management board — which stated that trash should be picked up on Seventh Ave. — to mean that all deliveries and pickups should be directed to Seventh Ave. and, ergo, was under the impression that the company wouldn’t be accepting deliveries on W. 16th St. anyway.

Meanwhile, about 50 renters living above Barneys remain without gas, after Con Edison inspectors found an “improperly installed” connection valve, which left three times that number of residents without gas in May, according to a New York Times report (“2 Businesses Reopen, But Tenants Upstairs Remain Without Gas,” Feb. 23, 2016).

The Times reported that Barneys asserted it had done its best to make good with the community, even providing residents with electric hot plates to tide them over until their gas started flowing.

“Barneys New York sincerely appreciates the patience demonstrated by all of the tenants of 161 West 16th Street during the build-out of our new downtown store,” the retailer said in a statement.

But for Groncki, who’s lived on the 100 block of W. 16th St. since 1987 and has grown familiar with both the old Barneys and the new, the long saga of the retailer’s many struggles with the community have taught him one important lesson.

“You can’t trust Barneys,” he concluded.