BY YANNIC RACK | Over the next few years, an imposing nine-story brick building at the corner of 11th Ave. and W. 20th St. will be transformed into the state’s first Women’s Building — a center for social activism housing a wide array of nonprofit women’s organizations.

With such a noble purpose in its future, the structure’s recent past stands out even more: until three years ago, 550 W. 20th St. was the site of the Bayview Correctional Facility, a medium-security women’s prison.

The building held 153 inmates when it was shuttered shortly before Superstorm Sandy made landfall in October 2012.

The women were evacuated and sent to other facilities upstate, but the 100,000-square-foot space, directly across from the Chelsea Piers sports complex, remained closed to save money. Once the transformation is complete — around 2020 — the Women’s Building will include a restaurant, an art gallery and some community space, possibly including a wellness center.

“We are envisioning a sort of vertical neighborhood where women leaders can connect with each other in very powerful ways,” Pamela Shifman, the executive director of the non-profit NoVo Foundation, said at a recent community meeting aimed at gathering ideas for the center’s use.

The foundation is partnering with Goren Group, a woman-owned and operated real estate development company, to transform the building, and a design competition was recently launched to find an architect for the project.

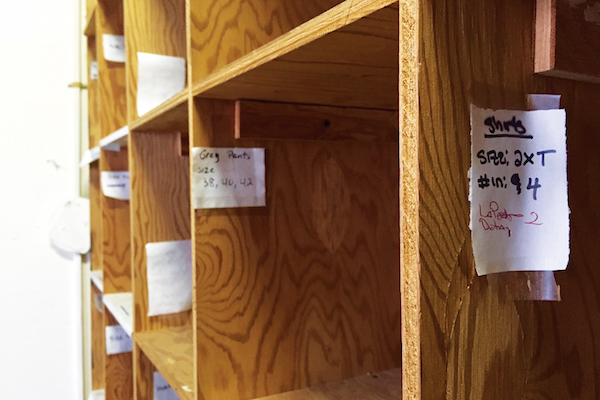

In addition to a first-floor gym and a fenced-in basketball court on the roof, cellblocks throughout the building remain (although many of them are gutted). In the room that once served as the library, ceiling paint has been slowly peeling off for years.

Now that plans for the building are underway, concerns have flared up once again in the community, where some vocal advocates have long pushed for landmark status for the building.

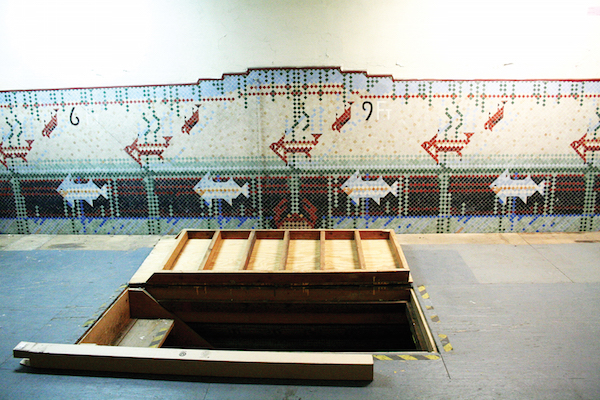

Only a prison since the late 1960s, it was originally built as a waterfront YMCA, serving the sailors and merchant marine crews working on the Chelsea waterfront with facilities such as a small chapel and a mosaic-stained pool — features that still exist today, although the pool has been covered over to serve as a storage space, and the chapel likely hasn’t seen much prayer in recent years.

“We’re happy not to see it become another anonymous luxury condominium that amounts to a fourth home for a billionaire who’s never even going to be present,” David Holowka, a member of Community Board 4’s Land Use Committee and an ardent admirer of the building’s nautical-style architecture, told Chelsea Now.

The Seamen’s YMCA was built in 1931 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, the architectural firm whose most famous creation, the Empire State Building, was finished that same year.

“The governor [in his announcement of the project] refers to it as an institution of defeat, with no reference whatsoever to the importance of the building to the neighborhood’s history — the working waterfront it represents and the history it embodies, which is pretty much written all over its façade,” Holowka said.

Inside, the chapel’s nautical wall mural and the pool’s aquatic mosaics remind one of the building’s earlier incarnation.

On the outside, the structure’s legacy is more subtle. The brick façade sports Art Deco massing, embellished terra cotta plaques and light fixtures that continue the seafaring theme.

The NoVo foundation says it is committed to preserving the building’s unique features, and will work with the state’s Historic Preservation Office on the redevelopment.

“We’re required to maintain some historical aspects,” Shifman told attendees of this month’s community conversation session in Lower Manhattan.

But back in November, she said the prison’s legacy was just as important to remember.

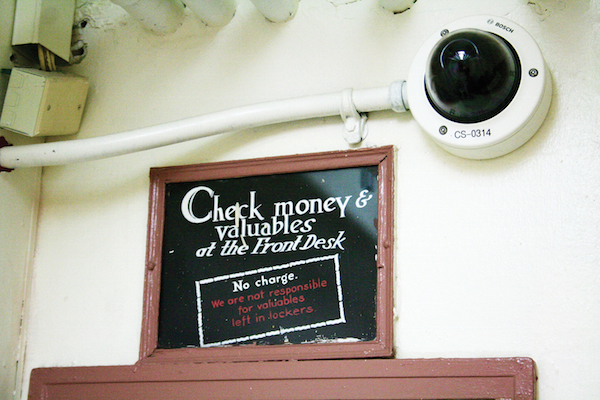

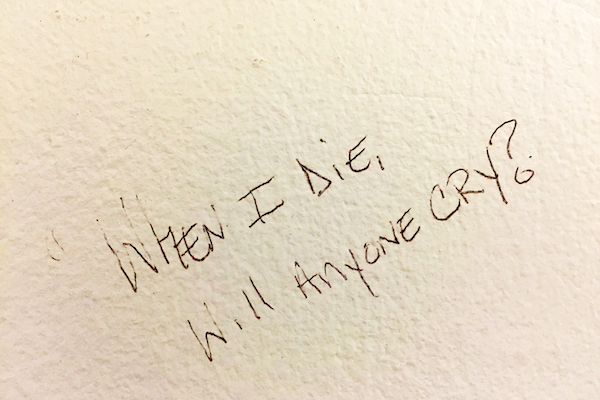

“We do know that we want to preserve key parts of the building to serve as a permanent reminder of what happened to women behind the walls of Bayview, and to educate everyone about what continues to happen to women in our criminal justice system,” she told Chelsea Now.

Bayview, in the early 1980s, became briefly notorious for being the site of widespread sexual abuse involving inmates and staff. In response, the corrections department disciplined offending staff and the prison’s entire executive team was replaced.

“We felt that it was an opportunity to turn a place that was about pain and confinement into a place that is about justice and liberation and freedom,” Shifman said.