BY KELSY CHAUVIN | Coinciding with LGBT Pride Month, the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Battery Park City has a new exhibit about the plight of gays during the Holocaust. “Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945,” which opened on May 29, examines the history of gay men and lesbians during Adolph Hitler’s regime as well as the German criminal statute that led to their systemic oppression.

“The exhibition explores why homosexual behavior was identified as a danger to Nazi society and how the Nazi regime attempted to eliminate it,” said exhibition curator Edward Phillips. “The Nazis believed it was possible to ‘cure’ homosexual behavior through labor and ‘re-education.’ Their efforts to eradicate homosexuality left gay men subject to imprisonment, castration, institutionalization, and deportation to concentration camps.”

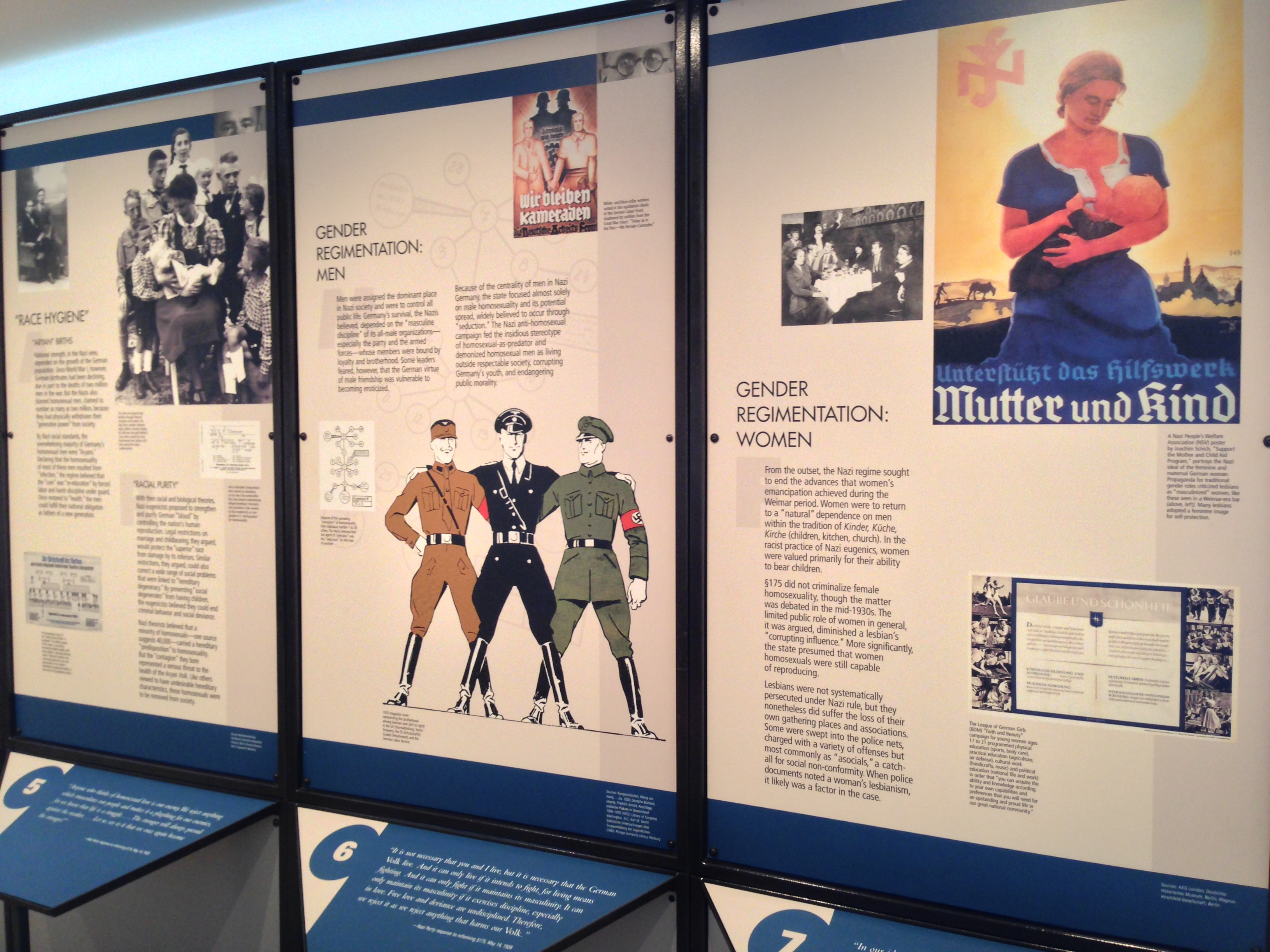

The traveling exhibit is on display in Lower Manhattan through October 2. It was produced by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org) in Washington, and consists of a series of panels organized according to phases in the persecution of gays over the 12 years of Nazi rule.

The panels cover topics beginning with the ascendancy of liberalism in Germany during the Weimar Era, from 1919 to 1933. As explained in the exhibit, those years brought to big cities like Berlin “rapid growth, social diversity, and a permissive atmosphere” that saw flourishing artists’ communities, as well as cafés, bars, and dance halls that allowed same-sex “friendship leagues” to form.

But that tolerant heyday vanished with the 1933 appointment of Hitler as chancellor. Armed with the 1871 German Criminal Code provision known as Paragraph 175, which criminalized homosexual acts between men, Hitler seized the opportunity to persecute those labeled as degenerates, alleging that they threatened the country’s “disciplined masculinity.”

The law did not apply to lesbians, and in general women were targeted less than gay men. The exhibit touches only glancingly on the treatment of lesbians, but notes that women were prized as wives and mothers for a nation that faced a declining birth rate. The lesbians who were persecuted were typically deemed “asocials,” a Nazi catchall term for non-conformity. Their stories are not well-documented, and thus are an obvious missing element of this exhibit.

In all, about 100,000 men were arrested for violating Nazi Germany’s anti-homosexuality statutes, and of these, approximately 50,000 were sentenced to prison. Somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 men were sent to concentration camps on similar charges, where an unknown number of them died. Other groups that suffered similar fates included the Roma (Gypsies), those with disabilities, Soviet prisoners of war, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

While the exhibit is educational and sorrowful, it manages to convey both the big picture of homosexual victimization and individual stories that offer elements of uplift, resistance, and even limited triumph. One of those is the story of Willem Arondeus and Frieda Belinfante, two out queer Dutch artists who joined the anti-Nazi resistance and eventually led a group that in 1943 destroyed a Nazi records office in Amsterdam.

Belinfante managed to escape by disguising herself in male drag, hiding in Switzerland and eventually emigrating to the United States in 1947. Arondeus, however, was captured and executed. His last message proudly stated, “Let it be known that homosexuals are not cowards.”

Individual stories like these are a key part of the mission at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, which calls itself “a living memorial to the Holocaust.”

“The mission of our museum has always been to tell the story of the Holocaust not from the point of view of the perpetrators, but from the perspective of the victims,” said the museum’s director, Dr. David G. Marwell. “This exhibition tells the story of lesser-known victims of Nazi persecution and is an important contribution to our understanding of the period.”

Part of that living legacy will unfold throughout June with several special events. Sundays in June at noon, the museum hosts “Yellow Stars, Pink Triangles,” a new tour of its core exhibition with a focus on the Nazi persecution of gays. The tours will be conducted on a walk-in basis.

In addition to the space devoted to LGBT exhibit itself, the Jewish Museum also provides reading and conversation areas with related books to further explore the suffering the LGBT community endured under the Nazi regime.

“Many people don’t know the full extent of the Nazi campaign to eradicate homosexuality,” said Marwell. “We look forward to shedding light on this important subject.”

“Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945” is on display at the Museum of Jewish Heritage (36 Battery Pl., at First Pl.) though Oct. 2. Open Sun.–Tues. & Thurs., 10 a.m.–5:45 p.m.; Wed. 10 a.m.–8 p.m.; and Fri. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Tickets are $12, $10 for seniors, $7 for students, and free for children under 12 (and Wed. 4-8 p.m). For tickets, visit mjhnyc.org or call 646-437-4202. For more information, visit mjhnyc.org/npoh.