BY LINDAANN LOSCHIAVO | In April, when two long-standing sidewalk sheds were being demolished at 24 Fifth Ave., passersby saw a curious sight — gay Moorish tiles, their blue, white and orange pattern still bright after several decades of subterranean slumber beneath a heavy blanket of linoleum, tar and parquet, forgotten layers of flooring from the outdoor extension of an old ballroom.

Suddenly, a house of history was lifting its petticoats.

How long had these twin encroachments stood like imposing bookends on either side of the Fifth Ave. entrance, decreasing the width of the pavement meant for pedestrians? And who made the decision to restore the space to its original dimensions, enabling, once again, a sweet sidewalk symmetry from W. Ninth St. to W. 10th St.?

As with most pre-war buildings in Greenwich Village, there is a short answer — and also the spectator’s saga, unfolding bit by bit.

Ridding the sidewalks of intrusive ornamental entrances, porticoes and kiosks has been an ongoing concern for lawmakers. When this main artery was first laid out in the early 1800s, the avenue was 100 feet wide, providing for a roadway width of 60 feet and sidewalks of 20.

Early on, New York City gave property owners permission to encroach 15 feet for stoops, gardens and the like. But, as traffic congestion increased, the city began to rescind permits. In April 1908, the Board of Estimate and Apportionment ordered all encroachments removed from Fifth Ave.

In 1925, the palatial Brevoort mansion (which had become the residence of the Charles De Rham family) was razed. On its site, the Fifth Avenue Hotel opened in 1926, designed in the Spanish Renaissance style by architect Emery Roth.

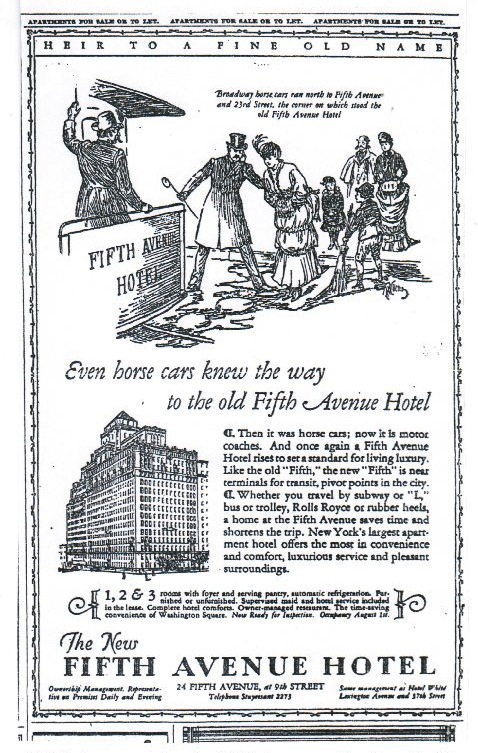

Their first announcements in The New York Times, introducing “the largest apartment hotel,” were bigger and more captivating than most; their creative pitches easily eclipsed those ho-hum print ads for tony Upper East Side residential apartment buildings.

Headlining the new hotel’s real estate notices as “Heir to a Fine Old Name,” the new owners of 24 Fifth Ave. saw no irony in this dichotomy — that they were promoting both the modern conveniences therein (i.e., automatic refrigeration, ice-making and serving pantries) along with the grand history of a manor house they destroyed.

For instance, one lavish piece captioned “The First Fancy Ball” stated: “The old Henry Brevoort residence, on the site of the new Fifth Avenue Hotel, was a society rendezvous in the Golden Age. America’s first masked ball, held here in 1840, was followed by an elopement which scandalized our worthy forefathers. From the time of the first masked ball, the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue at Ninth Street has been famous in the annals of New York’s society.”

A crisp pen-and-ink drawing of the building was paired with a finely detailed sketch of that infamous Valentine’s Day affair, when Miss Matilda Barclay (daughter of the British consul) slipped out with Mr. Burgwyne at 4 in the morning and, still costumed and masked, ran off to find a preacher.

Though it’s not recorded what refreshments the Brevoorts served at their frisky “Red Ball,” the newcomers wanted to assure prospective residents that “complete hotel comforts” were offered in the lease and an owner-managed restaurant would be available.

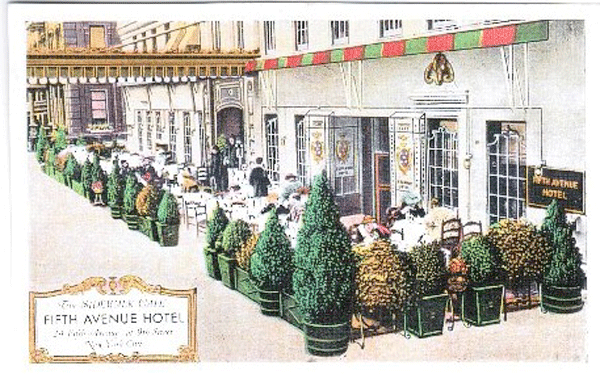

By the 1930s, the hotel operators were circulating hand-colored postcards showing an outdoor sidewalk cafe surrounded by shrubs in tubs and outfitted with red and green awnings. In bygone days, there was also a cocktail bar on the roof (adjacent to a children’s playground) and a smaller restaurant in the lobby’s rear called The Palm, details fondly recalled by veteran Village residents.

In 1972, after the building had been sold to Nathan Brodsky, the sidewalk eatery was permanently enclosed. When The New York Times food critic Raymond Sokolov visited Feathers, he called it an “elegant new café with varied fare,” praising its Baked Alaska and Cherries Jubilee and its vantage point that looked out on Fifth Ave. But his review criticized the restaurant’s policy of pay toilets (then located in the cellar not far from the kitchen), particularly out of kilter with the establishment’s plush Upper East Side décor.

By 1975, Feathers was a clear favorite with locals, thanks to one of its specials: a complete steak dinner for two with a glass of champagne for $10.

But other things did not go down as easily — including, for one, the landlord’s attempt to rent the ground-floor ballroom to a nightclub called Abracadabra. Luckily, the tenants found a reliable advocate in Greenwich Village Assemblyman Bill Passannante, who waved his legislative wand and made the noisy nightspot disappear.

Nevertheless, ongoing problems persisted. For instance, tenants who moved in during 1975 were given a standard two-year apartment lease and were informed that the hotel was being converted into a rent-stabilized building; a rider advised that hotel conveniences would be discontinued and individual electricity meters would be installed. But by 1980, the ownership had flipped its position, attempting to offer six-month hotel leases with higher increases. Because of these landlord-tenant disputes, a 24 Fifth Avenue Tenants Association formed and contentious monthly meetings in the lobby were a regular occurrence.

By August 1981, The New York Times was running articles like “Residential Hotel Dispute Builds.” Times reporter Lydia Long described these challenges and noted: “The tenants association at 24 Fifth Avenue is challenging the building’s classification as a hotel.” Long also observed: “But enough questions about classification of residential hotels have arisen to attract the attention of Attorney General Robert Abrams.”

Due to these disputes, petitions were circulated, pickets were organized and residents regularly reached out to the press, elected officials, the Conciliation and Appeals Board, and the Department of Buildings.

In 1978, when the landlord installed a bland enclosure in the lobby that covered the handsome cherub-and-garland-decorated entrance to the ballroom and eliminated a popular seating alcove, tempers flew. Shortly thereafter, when the ballroom’s sidewalk shed was being remodeled and equipped with outside doors, security-conscious tenants joined forces to summon building inspectors and complain to City Hall about the encroachments — that is, the two enclosed sidewalk cafe structures.

On Aug. 14, 1983, the Times ran an article with the headline, “Hotel Rent Rules Start Tomorrow,” explaining that “new restrictions effective tomorrow will limit the amount by which hotel operators may increase the rent for long-term tenants in rent-stabilized hotel rooms after they become vacant. The restrictions will affect about 35,000 dwelling units in 260 hotels… . ”

It took another frustrating decade before a lawsuit with numerous “complaining tenants” would be settled and the Brodsky Organization would issue leases with a legal rent.

The dichotomies linger at W. Ninth St. and Fifth Ave. When the management decided in April to demolish both sidewalk sheds and repave the sidewalk, it was said that they wanted to restore this landmarked building’s original appearance, with its tall French doors overlooking the avenue. Gossip among the long-term tenants has hinted about ulterior motives. But everyone seems happy to see that sleeping beauty of a hidden sidewalk returned to one and all.

Community Board 2 recently decided to approve a scaled-back sidewalk cafe permit for the building’s newest eatery, Claudette. The sidewalk cafe, per C.B. 2’s advisory recommendation, would have a smaller footprint than what was there before, and also obviously would now be unenclosed. However, the proposed outdoor light fixtures on the corner “have no precedent in the district,” according to C.B. 2.