BY Patrick Hedlund

If the painted pitch-black walls of the famed Pyramid Club in the East Village could talk, they’d also sing, laugh — and likely gag.

Ask anyone who spent time at the Avenue A nightspot about their experiences inside the historic venue, and you’re bound to be awed by tales of ribaldry and revolution, glamour and gaudiness.

It’s where performers named Brian and Jon became Hattie and Bunny, Hells Angels and skinheads mingled with filmmakers and drag queens, and creativity of all forms was honored above all else.

The confluence of those ideals — including the building’s early life as a social gathering space dating back to the 1800s — will help the property’s push to achieve landmark status after a local preservation organization recently undertook the effort.

As part of the Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation’s sweeping survey of the East Village, the group recently nominated the four-story tenement building at 101 Avenue A for landmarking after uncovering a wealth of history at the property dating back 130 years.

Once a social and banquet hall for German-Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the ground floor also acted as a place of merriment and mourning for the many Germans who lived in the East Village during that time. As the neighborhood transitioned through the years, the space kept pace by morphing into a music and performance venue while retaining its reputation as a cultural petri dish.

When it eventually became the Pyramid Club in 1979, the property had already served a century’s worth of patrons and organizers from the neighborhood. But its history going forward — and the prominent role the club played in promoting performance art — might be what eventually cements the Pyramid’s past on Avenue A.

“As we were doing this research, 101 Avenue A just jumped out at us,” said Andrew Berman, G.V.S.H.P. executive director, of his organization’s block-by-block East Village survey. “It’s in some ways one of the more extraordinary illustrations of what the East Village is all about.”

In their research, Berman and G.V.S.H.P. found the space originally housed the Kern’s Hall saloon after German-born architect William Jose oversaw its construction in 1876. From there, it became Shultz’s Hall, Fritz’s Hall and more famously Leppig’s Hall for a 30-year stretch. During its time as a meeting hall, it celebrated the opening of the adjacent Tompkins Square Park in 1879, acted as a gathering place for local laborers and unions, and memorialized the more than 1,000 people — many East Villagers of German descent — who died in the General Slocum disaster of 1904.

“It kind of mirrors the East Village,” Berman added of the building’s uses through the years, also noting the facade’s elaborately detailed cornice and stone-, iron- and brickwork.

When counterculture bohemians and artists starting replacing the East Village immigrant community in the 1960s, the space adapted by becoming a music venue catering to multiple genres. A cultural center and theater by 1979, the space changed hands again — this time calling itself the Pyramid Club.

The name, according to former creative director Brian Butterick, stemmed from the original pyramid design found in the building’s tiling.

“It still had the vestiges of that neighborhood bar when we ran it,” said Butterick, who helped lead the performance-art and drag scenes that eventually brought the club to the height of its popularity. “But we always forced a little art and controversy down people’s throats in the process.”

Butterick once performed at the club in drag as Hattie Hathaway and now runs Rapture Café and Books a few blocks north on Avenue A. He said the perception then of the Pyramid as gay bar was false, since it actually appealed to what he called a “polysexual” clientele.

“Every happening nightspot in Manhattan was run by gays in those days,” he said, calling the emergence of drag performances in the ’80s the “biggest social revolution” at that time. “It changed from specific female impersonations to female interpretation,” he said.

In fact, a “drunken party at 6 a.m.” in Tompkins Square Park, where clubgoers donned wigs at the impromptu show, evolved into the gender-bending Wigstock festival featuring famous drag performers RuPaul, Lady Bunny and Lypsinka.

“The Pyramid was the CBGB of drag and Downtown performance culture,” said Village Voice nightlife columnist Michael Musto, who covered the club “as a bastion of high camp, low culture and creative explorations.”

“It was a ramshackle place where struggling artists could take chances, make fools of themselves and create beautiful work,” Musto added. “A springboard for some talent that eventually went more mainstream, as well as just a place where anyone with some nerve could nab a spotlight and some onlookers.”

Bobby Anger, who was working behind the bar on a recent Friday night, started coming down from Connecticut to visit the club in 1985 and has worked there in some capacity since 1989. He remembers coming to the club during one of its notorious “Trip and Go Naked” parties — where clubbers waiting in line earned swift admission if they stripped down outside — and witnessing all forms of sexually explicit feats.

“There was the big discos and all that, but the Pyramid was something different,” Anger said. “It was about just having a place to perform. … You could be that individual, and nobody would say anything.”

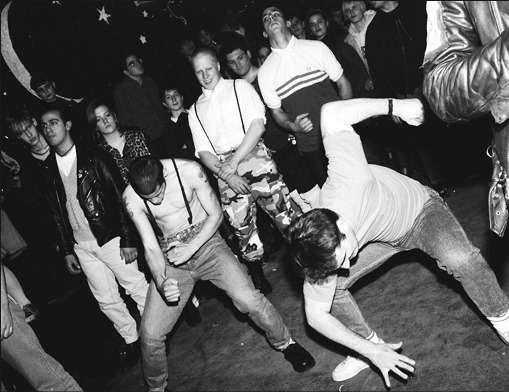

Performers considered at that time on the margins of socially palatable art sought refuge inside the Pyramid, which garnered an anything-goes reputation for allowing — and encouraging — experimental acts.

John Epperson, a.k.a. Lypsinka, started going to the Pyramid in 1984 and performed drag as well musical theater at the venue.

“When I went there, I realized it was the ’80s equivalent of what the gay baths had been 14 or so years earlier, launching the career of Bette Midler,” Epperson said. “I just knew in my bones this was the place to be. And there was a built-in audience on Sunday nights that loved everything, no matter how awful. It was O.K. to try anything.”

While many considered the Pyramid a gay bar, those who knew it best claimed the club simply catered to a more avant-garde and progressive crowd, which included people from all walks of life.

Lower East Side documentarian Clayton Patterson, who photographed the club and also presided over the Tattoo Society that met there monthly, said the Pyramid championed organic art, or “making creations out of nothing.”

“That was the magic of it,” he said of Hells Angels joining drag perfromers at the club and skinheads working the door. “That’s the kind of strange crossovers you would get. … It wasn’t about status, it was about creativity.”

Legend also has it that bands like Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers played their first New York City gigs there, joining acts like Madonna and Blondie, and further fermenting the club’s character as an artistic axis.

That rich history could play a deciding role in whether the property receives landmark status, said Lisi de Bourbon, a spokesperson for the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. She confirmed that the commission considers a building’s cultural, historical and architectural significance, but that it’s difficult to weigh these factors against each other.

A building’s social impact is “a difficult attribute to quantify,” de Bourbon said, adding that New York City properties have been landmarked based purely on cultural influence in the past. However, she did not comment on where the commission’s evaluation of the Pyramid currently stands.

A recent push to rezone the East Village could also affect this process, Berman noted, as a city assessment of the neighborhood’s historic resources would help bolster a landmark designation.

“[The neighborhood] definitely deserves much more attention,” Berman said, “and the commission is clearly now taking a look at the East Village.”

Today at the Pyramid Club, the bawdy performances have been replaced by themed dance nights, with gay men outnumbered by their straight gal pals, according to Anger. He claimed women now dominate the club’s most gay-friendly night, although a recent visit showed the men at least outpacing the women on the dance floor.

Musto said that while most clubs’ current marketing efforts aim at attracting a specifically gay or straight crowd, the Pyramid always has had “an overriding gay sensibility.”

“I think to some people it will always be considered a gay bar,” Anger acknowledged.

Those determinations, though, seemed lost on most who spent time at the Pyramid during its heyday. For them, it wasn’t about the diverse characteristics people brought into the club, but how they all coalesced inside.

Although Butterick no longer has any affiliation with the club, he still fondly reminisces about his time there and the cultural revolution he helped spawn. He even waxes spiritual about the historic space, predicting a continued dynamic future for the property.

“I think that walls and floors and the very land that something is on retains some of the soul of prior existences,” he said, adding that club regulars used to joke that the space sat on a former Indian burial ground. “I think that ghosts of the past live on there, so there will always be something happening there.”