BY LINCOLN ANDERSON |

In the wee hours one morning in the early 1980s, heading home after a euphoric night playing his congas at Crisco Disco in Chelsea, Novac Noury bought a newspaper. A listing for a building for sale on Little W. 12th St. caught his eye. He had been looking for a secret hideaway — a place where he could give performances on his arrow keyboard and also open an after-hours club. The location in the then-desolate Meat Market sounded like the perfect fit.

Plus, the building, 51 Little W. 12th St., was zoned for cabaret as well as adult use, only the former which he needed for his plans.

“It was a 24-hour topless and bottomless pit,” Noury said.

He bought the building and started evicting people.

Noury spoke as he gave a tour of the place — and told the quirky tale of the arrow keyboard — last Sunday.

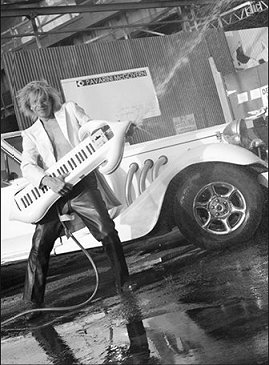

Back in the mid-1970s, Noury (prounounced Nor-ay), now 61, developed a patented wireless keyboard in the shape of an arrow (actually it was based on the Wrigley’s spearmint gum logo) that shot fire, shaving cream and water. Prancing about in a one-piece, tiger-print outfit and a mask while wielding the enigmatic instrument, he became a fixture on the disco scene. He would prop the keyboard against his crotch, while suggestively thrusting his pelvis and blasting out whatever substance — sparks, cream, H20 — fit the mood and music.

Yet, it was always intended as tasteful “sexual fantasy,” he said, adding that how he grasped the priapic piano was just the practical way to hold it.

“It’s the symbol of man,” he said of the keyboard’s arrow shape. “It’s man’s greatest moment,” he said of, well…what the arrow did.

He performed with his keyboard at Studio 54 and Odyssey 2001 — the club in “Saturday Night Fever” — and spurted cream with it onto a woman popping out of a cake at Magique at the birthday of Egon von Furstenberg, Diane von Furstenberg’s first husband. Noury had a cameo schpritzing sparks in the movie “Hair.” He became known as the Phantom of the Organ™.

Meanwhile, RSVP, his membership-only after-hours club, was enjoying success, too, raking in $25,000 a month at its high point. In his white limo, Noury would ferry partiers from Studio 54 to RSVP — the passengers quaffing champagne while disco favorites like “Born To Be Alive” blared from the tape deck — pulling right into his building via his driveway, which he dubbed, naturally, “Arrow Way.”

Noury’s building had a platform extending to the High Line on which the revelers would sometimes sit on summer mornings while Noury cooled them off with splashes of water — not from his arrow keyboard — but from a hose.

But after being seriously injured in a car accident in 1990 and the tragic Happy Land social club fire — the latter which he felt was a warning from above — Noury closed RSVP. Today, the only hints of the building’s former glamorous life are the “hieroglyphics” on its “secret marquee,” as Noury described it — arrow keyboards and hearts (which he said symbolize woman) that he carved into cement on its exterior.

Secret is exposed

But now Noury and his undercover building find themselves exposed — right in the middle of a major boom in the Meat Market. With its structure already rising 10 stories tall, Andre Balazs’s new Standard hotel is going up just north of Noury’s place. A 250-foot-tall crane looms high in the air directly above Noury’s second-floor terrace, which offers an up-close view of the bridgelike portion of Balazs’s hotel spanning the High Line.

Not to be outdone, however, Noury has development plans, too. He’s looking for a partner to help him put up a 10-to-12-story “mini-inn” on his property with an unusual, eclectic mix of uses. Like Balazs’s hotel, Noury’s building is outside the Gansevoort Historic District, so the construction doesn’t face landmark restrictions.

Noury is conceptualizing a 40-room mini-inn. It would have three restaurants, a stem-cell research area and a physical therapy center, crowned by a pyramid-shaped greenhouse that, as Noury said, would “blink to the ships.” This pyramid also would have “RSVP” technology, or rechargeable solar-powered Venetian blind energy — in which metal blinds in a high-tech liquid substance would collect solar rays — yet another pending Noury invention. A waterfall would provide privacy between his mini-inn and The Standard.

It’s an ambitious project, to say the least.

For the moment, though, Noury is focused on restoring his connection to the High Line, since Balazs demolished the platform that used to connect Noury’s building at its fourth floor to the old elevated tracks. This connection, Noury says, would be called “The Stairway to Highline” — a riff on Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.” He envisions a Parks Department employee cranking a drawbridge up and down to allow access. Conversely, when people would use it to walk from the High Line to Noury’s property, it would be known as “The Stairway to History.”

Indeed, there’s history to Noury’s building, which was constructed by the Astors in 1855. Noury said when he excavated his basement — which had been filled with dirt — he discovered two bricked-up arched doorways, which he later concluded were “secret tunnels” to Pier 54 at W. 13th St. Also uncovered was a massive, 60-foot-long, 1911 Wells Fargo safe. Putting two and two together, he figured the tunnels must have been how the Astors moved their money from the dock to the building.

“It just stands to reason,” he said, “if there’s a safe and tunnels to Pier 54. … If there’s a family dealing in international trade, how do you get your money out?” Local preservationists are skeptical of his version of the tunnels’ history, however.

Not selling anything

He said Stephen Touhey, who unsuccessfully tried to develop a 500-foot tower on the old Nebraska Beef building site before Balazs, offered to buy Noury’s air rights.

“He said, ‘We’ll give you an easement till you die,”’ Noury said. “I said, ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’ I’m here for a legacy of the history and mystery of the building. It’s a music building. It’s a timeless museum. I represent the telecommunications era with my wireless keyboard.”

On the other hand, Noury said the owners of the two buildings to the west of his did sell their air rights to The Standard.

He said Diane von Furstenberg, before she found her new location on 14th St., called, offering to buy his property.

“She said, ‘Dahling, I know you’re not going to sell. …’ I said, ‘You’re right,’” Noury recalled.

Noury has invited David Rabin, the owner of Lotus and president of the Meatpacking District Initiative, to partner with him on the mini-inn.

“I said, ‘Let’s build a hotel with three restaurants, steak and lobster. …’ Rabin said, ‘Let me get back to you’ — never called me,” Noury recounted.

Noury’s place is full of collector’s items from the music and club scene and beyond. Much of it is stored in his basement, including the rock band Mountain’s sound equipment, a mannequin from the former Mineshaft S&M club — “I cleaned it, disinfected it and painted it silver,” he noted — the pool table from “The Hustler” — “It’s the one Paul Newman’s knuckles were cracked on” — and a carousel horse from Gimbel’s.

Recalling the racy RSVP days, Noury said, “When the American Ballet and Joffrey Ballet came here, they would get on the horse and disrobe a bit and do their moves — modern jazz of course.”

There are tweeters from the old Village Theater, the predecessor to the Fillmore East, where Noury led the house band, opening for the likes of The Doors, Vanilla Fudge and Jimi Hendrix. One night he played background organ as LSD guru Timothy Leary held forth.

“Instead of doing acid, he demanded a fifth of Segram’s 7,” Noury said.

Noury wasn’t into blowing his own mind, although he soon had a vision — of the arrow keyboard, which he said was inspired by “jealous envy” after watching Hendrix perform.

Noury grew up in East Flatbush, honing his musical chops singing at Brooklyn Heights’ Grace Church. His real name is Jerry Lewis Noury, but he adopted Novac, inspired by actress Kim Novak and a computer of the same name, and because it sounded catchy before Noury.

In his earlier musical days, one of his groups, the Ebbtones, had a local hit with a dance tune, “The Wobble,” a form of which he said he sees lots of young people doing nowadays, ironically.

As for 2007’s teeming nightlife, Noury said it has “exploded immensely” compared to the disco days. “There’s a club on every block,” he said. He doesn’t like the fights, though, that he says he sees up by “the triangle” in the Meat Market.

“It’s not as creative,” chimed in his girlfriend, Hanah White, regarding today’s club scene, as she listened in on the interview. In 1993, she worked the door at the Roxy club in a white wedding dress.

Speaking of nightlife, Noury said he was contacted by Ivan Kane, who wanted to put his Forty Deuce 1920s-style burlesque cabaret in Noury’s building.

“He wanted to rent out my grandfathered cabaret,” Noury said. “I will not have a burlesque-type atmosphere in my building. My keyboard invention, as you know, is very controversial. I would not want to make myself totally X-rated.”

Kane is trying to open Forty Deuce on Kenmare St. instead, but is facing community opposition.

So far, Noury hasn’t heard back about his inquiries on restoring his “Stairway to Highline” connection. He said he asked the Friends of the High Line about it and was told, “Go to the Parks Department.” He reached out to Michael Bradley, the High Line Park’s administrator, which hasn’t yielded results either. However, Noury has been notified that property owners who want an entrance to the High Line should act fast, because delaying will increase the cost.

‘Buildings are bouncing’

Noury’s most pressing concern right now is that the construction work on The Standard has been causing cracks on his building, as well as on neighboring buildings. Noury has requested crack monitors to be placed over the fissures to gauge if they’re spreading. Every weekday, Noury hangs over his patio wall and anxiously videotapes as belching backhoes and drills bang near his building.

“The buildings are bouncing every day,” he said. “Andre Balazs does not know what is going on here. It’s not going to look good for Balazs” if an accident occurs, he added.

If his building survives the construction next door, Noury feels he has a lot to offer — particularly to the High Line. He can see himself firing water — but not shaving cream — from a giant arrow keyboard onto passersby on the High Line to cool them in the summer, since he knows from experience how hot it will be up there. He’d also like to do weddings on the old tracks, complete with cars, if he can figure a way to get cars up on it.

Cars?

“The High Line needs fanfare,” he said.