By Melanie Brooks

Photo by Erika Blanco

In a recent competition at the White Box gallery in Chelsea, Serbian artist Dusanka Komnecic won the free legal services of New York immigration lawyer Daniel Aharoni, who will help her obtain an O-1 visa, good for three years.

The White Box in Chelsea felt more like a prison than an art gallery last month, when 8 foreign artists were quarantined for five days as part of an interactive art show and contest put together by Berlin-based Wooloo Productions, a non-profit artist collective.

The experiment, “AsylumNYC,” pitted the artists against each other for the chance to win free legal services from Daniel Aharoni, an immigration lawyer in New York City who will help the winner obtain an O-1 visa, good for three years. Last year the U.S. distributed roughly 6,000 O-1 visas, which are granted to foreign professionals based upon proven extraordinary ability in their chosen field. Only a small proportion of O-1s are given to artists, however, which helps explain the number of applicants— 235 artists from 43 countries— who vied for the chance to receive one. Only 10 were selected to compete in the show, but two didn’t attend, either because of travel difficulties or because they felt the show was exploitative.

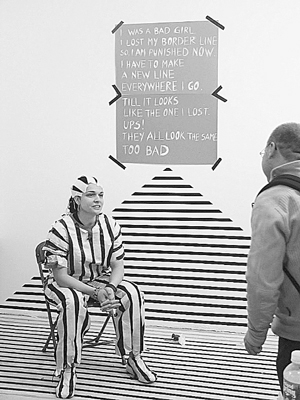

Curated at a time of heated debate on immigration rights, AsylumNYC aimed to explore the challenges faced by foreign artists working illegally in the U.S., namely the inability to travel into and out of the country. The rules imposed by Wooloo — essentially an exaggeration of the restrictions placed on foreign artists — were simple and strict. The artists could not leave their designated spaces. Their belongings were confiscated, and they were given an army green AsylumNYC t-shirt to wear. They couldn’t shower and had to ask permission to use the bathroom. A skinny mattress worthy of a jail cell was provided to each artist, and the food was similarly lean. Breakfast consisted of oatmeal. Lunch and dinner was a bowl of canned beans.

“They’ve given me plenty of reasons to be angry, but I understand this is a performance,” said Valeria Cordero, a 23-year-old photographer from Venezuela. She has been living in New York since 2001. Her student visa expires in June.

The artists were required to create a work of art that actively challenged the notion of exclusion in the U.S. To do this they were given only a pen and some paper. How they created their project and what it was made of was left to the mercy of gallery visitors, who in some cases provided the artists with supplies.

The winner, Dusanka Komnecic of Serbia and Montenegro, stood out from her peers in her adaptation to the imposed rules. Komnecic used black and white tape, which she got from visitors, to expand her imposed boarders into a path that, by the end of the week, reached outside of the gallery.

“She manipulated the rules without breaking them,” said Martin Rosengaard, director of Wooloo Productions. The free legal services couldn’t have come at a better time for Komnenic, who has been working as a visual arts teaching assistant at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee on a student visa that expires in July. Overwhelmed with the thought of being able to stay in the U.S., Komnecic wasn’t sure when she would trade Milwaukee for Manhattan.

Wooloo Productions had planned on awarding just one winner with free legal services, but by the end of the week it made an exception for Antonio Rubio. The Mexican artist couldn’t secure the necessary documents in time to participate in the contest, but his e-mail campaign reached the ears of Martin Liu, an immigration lawyer who offered his services to Rubio free of charge.

So what will become of the seven remaining artists, who competed in the exhibit but didn’t win legal aid?

Some, like Roman Lystvak from the Ukraine, seemed unconcerned. “I’m not doing this so much for the visa but more to say something,” said Lystvak, whose student visa expires in 2008. “I’m better off than most of the other artists here.”

But Valerie Cordero, for one, is worried. In August, she will leave New York and head to Berlin for three months to participate in an artists’ residency. She hopes that by the end of the year she will have obtained an O-1 visa to return to the city. If not, she will most likely stay in Berlin and try to find opportunities abroad.

“The artist’s visa is very difficult to get,” Cordero explains. “What does ‘having extraordinary ability’ mean? How do you prove you have it? I do not know the answer to those questions, but that visa is my best chance at staying in the U.S…. I do not want to go back to Venezuela. I love my country very much, but right now we are going through some dark times politically, economically, and socially, and I just don’t want to be in the middle of it.” Cordero said.

Nao Matsumoto, a Japanese sculptor, has been living in Brooklyn for seven years, first as a graduate student at Pratt and then as an employee with an H-1 visa.

“I have been struggling way too long to find a way to obtain a visa,” Matsumoto said. He has been working for three years under the guise that when his H-1 visa runs out next year, his company will help him obtain a green card. But Matsumoto’s employer has recently reneged on their promise.

“Realistically I need to find a way to get an O-1 visa myself,” said Matsumoto.